Explore | Collect | Design

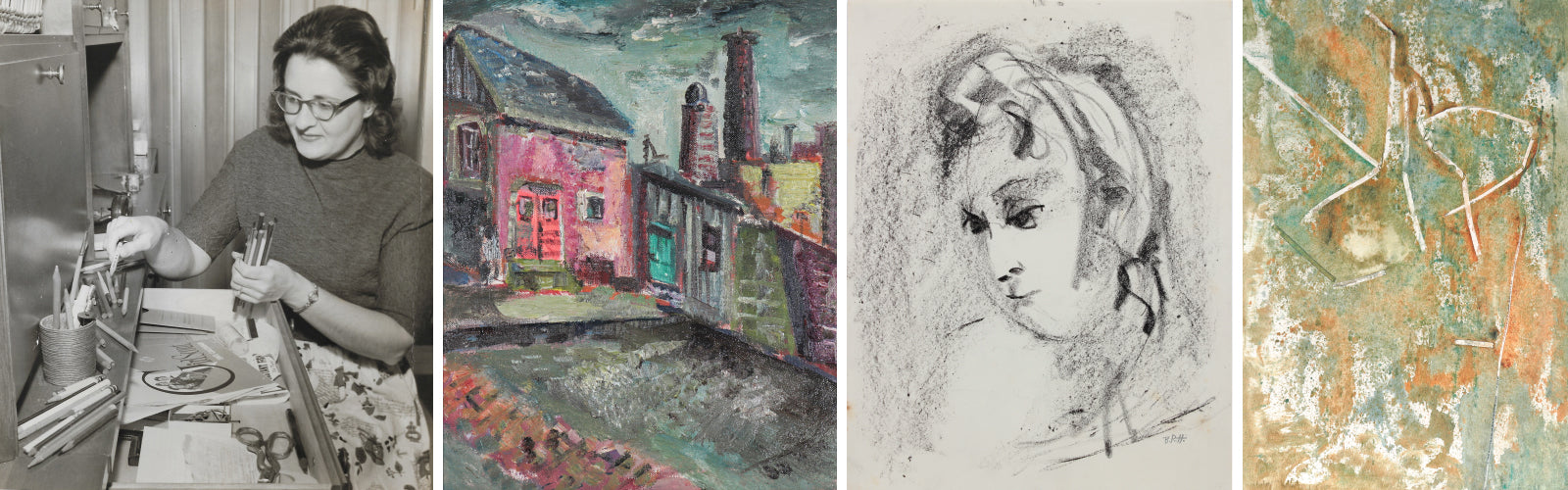

Barbara Rogers Houseworth

| Previous Artist | Next Artist |

Barbara Rogers Houseworth (1925-2015)

-

Play, intimacy, and experimentation --- these are the words that come to mind when encountering the prolific work of Barbara Rogers Houseworth. From dynamic experiments in abstraction, to textured street scenes of children basking on their stoops, as well as loose and expressive portraits and ink sketches of her young daughters, Barbara’s work is characterized by a keen attention to childhood, adolescence and ultimately, motherhood.

Play, intimacy, and experimentation --- these are the words that come to mind when encountering the prolific work of Barbara Rogers Houseworth. From dynamic experiments in abstraction, to textured street scenes of children basking on their stoops, as well as loose and expressive portraits and ink sketches of her young daughters, Barbara’s work is characterized by a keen attention to childhood, adolescence and ultimately, motherhood.

A Midwestern Mary Cassatt, Barbara’s playful and stylized renderings of mother and child scenes, as well as her many other portraits, mostly of young women, teeter between the whimsical and the soulful. Heavy lidded half-dollar eyes imbue each figure with a tinge of melancholia, a frequent trope in her work inspired, she claimed, by one of her instructors the artist, Steve Greene. By depicting the nuances of home-life, documenting her children’s growth through her work, as well as her own psyche through her portraiture, Barbara’s paintings provide an intimate window into the world of a 1950’s housewife. Homemaking and mothering were not recognized as “real” labor in that era and many artists who entered into motherhood were faced with the prospect of having to sacrifice their art practice. Forging the time and space to create such a prolific and personal body of work under these domestic pressures is a testament to Barbara’s zeal and dedication to art making. Yet, it is these very pressures that constitute much of the inspiration for her work.

Born August 11th, 1925 in Indianapolis, Indiana, Barbara Rogers Houseworth showed an interest in art at a very early age. She was raised in Bloomington, Indiana, where both her parents had lived for generations. Her parents supported her artistic inclinations with her father often bringing home large sheets of newsprint for Barbara to draw on. She would spend hours sprawled across the floor of her parents’ bedroom, just drawing and doodling – on some occasions it was girls’ faces, others it was creating her own paper dolls with interchangeable paper clothing, and sometimes it was simply whatever bloomed in her vivid imagination.

Barbara continued to paint in high school, where she first encountered oil painting. This rich medium would soon take on a prevalent role in her practice during her college years. In 1943, Barbara enrolled at Indiana University pursuing a degree in Fine Art, which at the time was just beginning to expand its art department under the guidance of art critic and historian, Henry Radford Hope (1905-1989). Here, Barbara was able to hone her technical skills and expand her creative prowess under the tutelage of artists Harry Engel (1901-1970) and Steve Greene (1917-1999), each of whom painted in the social realist and abstract style in vogue during the mid-century.

She was keenly involved in university life, working summers in the art department's office and the library, and during the war years was entrusted to run the office on her own one summer. She also involved herself by joining an artist’s student group known as ‘The Dauber’s Club.’

June 15th 1946, the day of her graduation ceremony, Barbara married John Horace Houseworth, a medical student at Purdue University. For the first six years of their marriage, they lived in Indianapolis, settling into their first apartment as a wedded couple. Barbara and John soon welcomed their first daughter into the world, Ann Rogers Houseworth, born in 1948. Barbara continued to paint and exhibited at the John Herron Art Museum from 1945 to 1955, often featured in shows alongside other Indiana based artists. Her husband’s medical career transported them briefly to San Antonio, Texas and Aurora, Colorado, until finally settling in Urbana, Illinois in 1954.

That same year marked the arrival of her second daughter, Susan Lee Houseworth. The advent of Susan’s birth sparked a revived creative outpour for Barbara, marked by the numerous paintings and drawings of her daughters and scenes from their domestic life. Humorous and playful, the sketches and paintings from this period in Barbara’s life are not concerned with naturalistic rendering. Instead, they capture the whimsy and essence of childhood through loose bold line work and simplified forms. They represent the inner world of both mother and child, a subject often excluded from the artworld during this period. In a post-war era that was characterized by a surge in suburban domestic life Barbara’s work stands as a testament to an aspect of Americana that was largely kept behind closed doors.

These intimate depictions of domestic life and motherhood represent a large portion of the acquired works in the Lost Art Salon collection, and are characterized by their whimsy and surrealistic quality. In addition to these, the collection holds many of Barbara’s textured, energetic, and colorful landscapes, dating to the 1940s, and a selection of her early more traditional and representational paintings from her undergraduate studies at Indiana University. Her portraiture and still lifes from this fledgling period exhibit Barbara’s keen eye and visual talent. They embody the social realist painterly style predominant in American art from this wartime period, via their subdued palette, textural brushstrokes, and naturalism.

Amongst the representational pieces, stands out a small group of intricate abstract pieces. Barbara’s foray into abstraction during her university years continued to be a part of her painting world and she often began with playful abstract experiments that allowed her to expand her imagination and spark further creative explorations.

As her children left the nest, Barbara gradually turned away from painting and drawing. As her focus shifted to collecting antiquarian and vintage books, most of her artworks remained largely unseen gathering dust in the garage of their Illinois home. Her work was rediscovered by her daughters towards the end of Barbara’s life and celebrated in a retrospective of Barbara’s work exhibited at the Madden Arts Center in Decatur, Illinois, in March 2020.

Lost Art Salon is delighted to represent the work of Barbara Rogers Houseworth and extends our gratitude to her daughters, Ann Massing and Susan Houseworth, for allowing us to share Barbara’s work and preserve her legacy.

Modernist Fruit Still Life

1943-46 Oil

#B0837 Barbara Rogers Houseworth (1925-2015) Sold $1,195

1943-46 Oil

#B0837 Barbara Rogers Houseworth (1925-2015) Sold $1,195

Sold

Composed Portrait of a Woman

1943-46 Oil

#B0804 Barbara Rogers Houseworth (1925-2015) Sold $595

1943-46 Oil

#B0804 Barbara Rogers Houseworth (1925-2015) Sold $595

Sold

Surreal Abstracted Form

1957 Mixed Media

#B0781 Barbara Rogers Houseworth (1925-2015) Sold $195

1957 Mixed Media

#B0781 Barbara Rogers Houseworth (1925-2015) Sold $195

Sold

Subscribe

Sign up to learn about new collections and upcoming events