Explore | Collect | Design

Hope Meryman

| Previous Artist | Next Artist |

Hope Brooks Meryman (1931-1975)

-

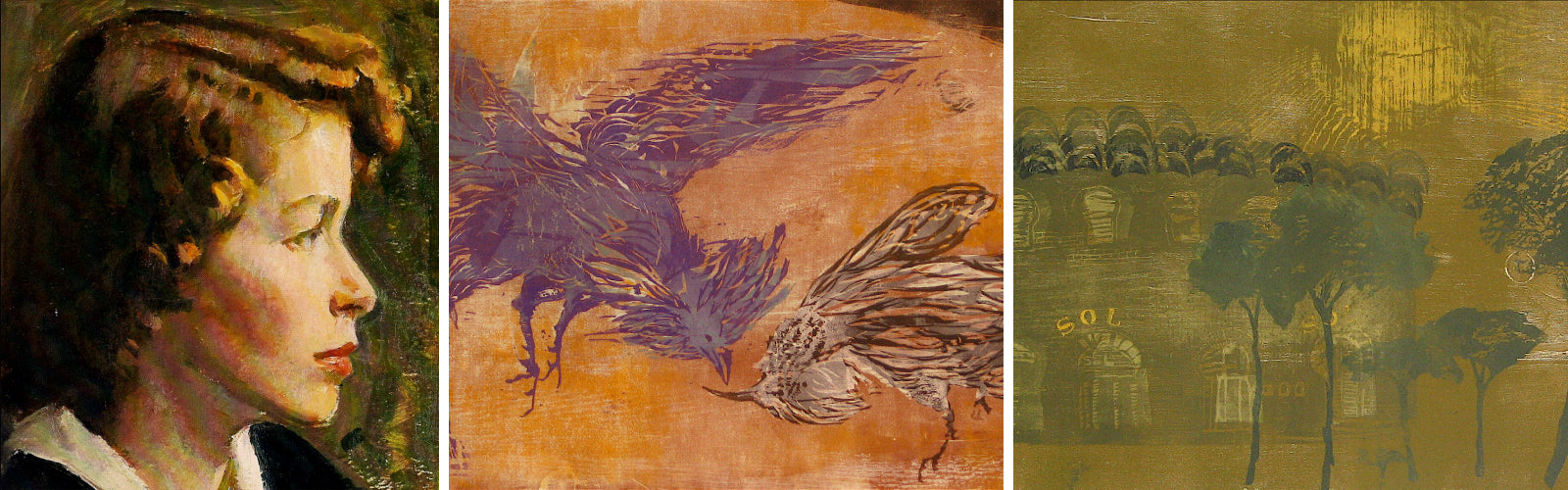

This group of woodcuts on paper by Hope Brooks Meryman were made during her all too short art career in New York City in the 1960s. Meryman was a master at capturing the feeling of a moment, the atmosphere of a particular place or the character of an individual. She cut little moments into large-scale woodblocks, giving them a timeless and iconic presence. Her life in New York City, her vacations to New England and her travels to the Mediterranean informed much of the imagery in her work. Hope sketched on location, then transformed her drawings into woodcut prints in her studio by using the traditional method of hand-rubbing each edition. Hope passed away in her early 40s.

This group of woodcuts on paper by Hope Brooks Meryman were made during her all too short art career in New York City in the 1960s. Meryman was a master at capturing the feeling of a moment, the atmosphere of a particular place or the character of an individual. She cut little moments into large-scale woodblocks, giving them a timeless and iconic presence. Her life in New York City, her vacations to New England and her travels to the Mediterranean informed much of the imagery in her work. Hope sketched on location, then transformed her drawings into woodcut prints in her studio by using the traditional method of hand-rubbing each edition. Hope passed away in her early 40s.

During her lifetime, Hope Meryman's work was shown by the Carus, Greenwich and Associated American Galleries in New York. She exhibited extensively across the country, including the Library of Congress, the Print Club of Philadelphia, Silvermine, and the American Watercolor Society. She illustrated several books, including "Akimba and the Magic Cow", "Why the Sky is Far Away", and "One Summer". Meryman studied extensively with Antonio Frasconi, John Groth, Seong Moy and George Grosz.

A passion for art continues in her family. Today, her sister Meredith Brooks Abbott is a well known member of the Oak Group of artists in the Santa Barbara area of California. And her sister, Whitney Brooks Hansen, continues to paint and make woodcuts in Long Island, New York.

The following was written by Hope’s surviving husband, Richard Meryman, author of "Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life":

Hope Brooks Meryman, known as Hopie, was born in Los Angeles in 1931. She was the very definition of a commitment to art. Her father, Robert Brooks, contributed an art gene. During World War I, with no art training whatsoever, he illustrated his letters to his wife, Hope, with superb and witty pencil drawings portraying how much he missed her: a knight in armor pulling an arrow from his chest. In 1945 Brooks moved the family to the semi-isolation of a self-sufficient dry-farmed bean and lemon ranch outside the small town of Carpinteria, CA. He also raised sheep on San Miguel Island. Hopie's little brother Bobby followed his father into farming. Hopie and her three younger sisters--Palmer, Whitney, and Meredith--created for themselves a little world of creativity, a self-made hothouse of art. Their idea of a game was one sister describing a picture from a magazine and the others blindly drawing it. The closest image won that round. At birthday parties the table was a platform for super-elaborate creations: a cutout portrait of Meredith as Alice in Wonderland which was surrounded by all her animals. At their colleges, the sisters majored in art, Hopie at Connecticut College with one year at Scripps. All ended up as full time artists.

In 1945 Brooks moved the family to the semi-isolation of a self-sufficient dry-farmed bean and lemon ranch outside the small town of Carpinteria, CA. He also raised sheep on San Miguel Island. Hopie's little brother Bobby followed his father into farming. Hopie and her three younger sisters--Palmer, Whitney, and Meredith--created for themselves a little world of creativity, a self-made hothouse of art. Their idea of a game was one sister describing a picture from a magazine and the others blindly drawing it. The closest image won that round. At birthday parties the table was a platform for super-elaborate creations: a cutout portrait of Meredith as Alice in Wonderland which was surrounded by all her animals. At their colleges, the sisters majored in art, Hopie at Connecticut College with one year at Scripps. All ended up as full time artists.

In 1951 Richard Meryman, Jr.--the son of the portrait and landscape artist Richard Meryman and a correspondent for Life Magazine in its Los Angeles Bureau--was brought by his cousin to meet the ravishing Brooks girls. Hopie was driving out as the two drove in. Richard was galvanized by this beautiful, smiling redhead, framed by the car window and radiating charm. They began regular weekends together in Carpinteria and Santa Monica. In 1953 they were married just before he was transferred to Chicago. There she took a correspondence course in watercolor. Her closest female friend was an illustrator and at the kitchen table Hopie experimented with that craft.

In 1956 Richard was promoted to editor and brought back to New York, the capital of the arts for Hopie. Her compulsion went into high gear. Soon she was studying at the Arts Students League. Her life drawing class was taught by John Groth, the book illustrator and noted World War II artist for the Chicago Sun. His works are in the collections of New York's Metropolitan Museum and Museum of Modern Art, among others. John became Hopie's mentor, companion on sketching expeditions, and close friend.

Hopie also studied at Pratt Graphic Art Center taking classes from the German artist, George Grosz, and from the distinguished graphic artist Seong Moy who introduced her to wood block printing, giving her all the necessary tools, the ink rollers, knives and scoops. She joined a workshop where she was surrounded by engravers and lithographers. She talked technique with her father-in-law who had been head of the art school at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.--and he painted her portrait. Two other major mentors and influences were Antonio Frasconi and his wife Leona Pearce. Antonio is one of America's foremost wood block artists, depicting poetic landscapes and social commentary. Leona's prints shared Hopie's signature fascination with the joyous innocence of children at play. She and Richard adopted two girls, Meredith and then Helena. Leona was Godmother to Meredith.

In 1973 much freckled Hopie was diagnosed with malignant melanoma. For two years she gradually declined, each month interrupted by weeks of devastating chemotherapy and recovery. Facing death and the anguish of leaving her children, she was a masterpiece of fortitude and fatalism, importantly powered by her life preserving drive to make art. She took a course in lithography. She did her second Scholastic book. Only months before her death in December 1975 the one thing she wanted to do--and did--was a painting trip to the divided French and Dutch Carribean island of St. Martin. One day very near her death she sat in her studio trying to draw, encouraged by two of her many friends, one holding her erect in her chair. Her artist sister Meredith once asked, "How can you do it? How are you doing all this?" Hopie answered, "The only thing I can think that makes any sense is that you build up some kind of platform for your children and leave behind you a body of work."

Subscribe

Sign up to learn about new collections and upcoming events

This group of woodcuts on paper by Hope Brooks Meryman were made during her all too short art career in New York City in the 1960s. Meryman was a master at capturing the feeling of a moment, the atmosphere of a particular place or the character of an individual. She cut little moments into large-scale woodblocks, giving them a timeless and iconic presence. Her life in New York City, her vacations to New England and her travels to the Mediterranean informed much of the imagery in her work. Hope sketched on location, then transformed her drawings into woodcut prints in her studio by using the traditional method of hand-rubbing each edition. Hope passed away in her early 40s.

This group of woodcuts on paper by Hope Brooks Meryman were made during her all too short art career in New York City in the 1960s. Meryman was a master at capturing the feeling of a moment, the atmosphere of a particular place or the character of an individual. She cut little moments into large-scale woodblocks, giving them a timeless and iconic presence. Her life in New York City, her vacations to New England and her travels to the Mediterranean informed much of the imagery in her work. Hope sketched on location, then transformed her drawings into woodcut prints in her studio by using the traditional method of hand-rubbing each edition. Hope passed away in her early 40s.  In 1945 Brooks moved the family to the semi-isolation of a self-sufficient dry-farmed bean and lemon ranch outside the small town of Carpinteria, CA. He also raised sheep on San Miguel Island. Hopie's little brother Bobby followed his father into farming. Hopie and her three younger sisters--Palmer, Whitney, and Meredith--created for themselves a little world of creativity, a self-made hothouse of art. Their idea of a game was one sister describing a picture from a magazine and the others blindly drawing it. The closest image won that round. At birthday parties the table was a platform for super-elaborate creations: a cutout portrait of Meredith as Alice in Wonderland which was surrounded by all her animals. At their colleges, the sisters majored in art, Hopie at Connecticut College with one year at Scripps. All ended up as full time artists.

In 1945 Brooks moved the family to the semi-isolation of a self-sufficient dry-farmed bean and lemon ranch outside the small town of Carpinteria, CA. He also raised sheep on San Miguel Island. Hopie's little brother Bobby followed his father into farming. Hopie and her three younger sisters--Palmer, Whitney, and Meredith--created for themselves a little world of creativity, a self-made hothouse of art. Their idea of a game was one sister describing a picture from a magazine and the others blindly drawing it. The closest image won that round. At birthday parties the table was a platform for super-elaborate creations: a cutout portrait of Meredith as Alice in Wonderland which was surrounded by all her animals. At their colleges, the sisters majored in art, Hopie at Connecticut College with one year at Scripps. All ended up as full time artists.