Explore | Collect | Design

Saul Lishinsky

| Previous Artist | Next Artist |

Saul Lishinsky (1922-2012)

-

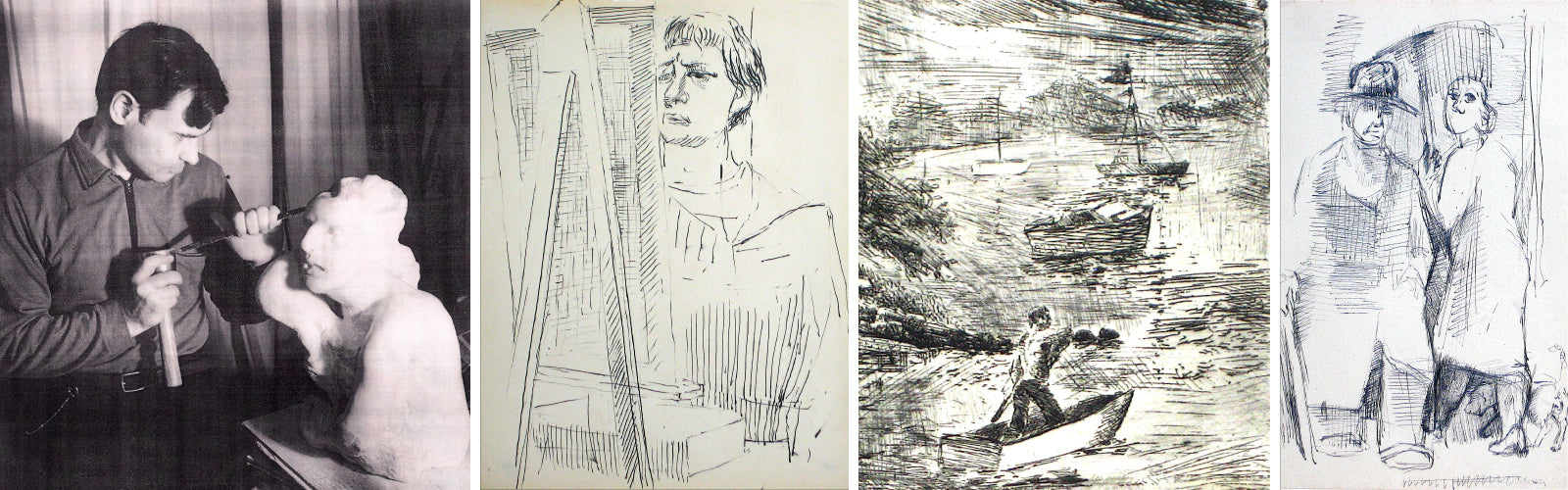

Saul Lishinsky was born in 1922 in Carbondale, Illinois. His Russian-Jewish family later moved to the Bronx, and Lishinsky remained in New York City for the rest of this life. Lishinsky served in WWII, and several pieces in the Lost Art Salon Collection feature imagery from his experiences on the front.

Saul Lishinsky was born in 1922 in Carbondale, Illinois. His Russian-Jewish family later moved to the Bronx, and Lishinsky remained in New York City for the rest of this life. Lishinsky served in WWII, and several pieces in the Lost Art Salon Collection feature imagery from his experiences on the front.

During the Summers of 1946-1948, Lishinsky studied in Provincetown with Hans Hoffman, and attended the Art Students league in New York City. His cousin, WPA painter Abraham Lishinsky, encouraged his art and he found inspiration in the works of Rembrandt and Cezanne- evidence of both are seen in his portraits and scenes of the New York working-class, laden with strong lines and attention to light and shadows.

Lishinsky had his first show at the 44th Street Gallery in 1946. He would later have eight one-man shows throughout the 1960s. He last exhibited at the Westbeth Gallery in 2006.

He counted amongst his close friends, important artists of the day including; Alice Neel, Phillip Reisman, Anthony Toney, Joseph Soloman, John Krucman, Louis Harris and Theo Fried. He was known as a social activist and founded the Bronx Community Murals project. Prominent murals by Lishinsky can still be seen throughout the greater New York City area. He was also a published poet, and in 1958 published his drawings and poems in a collection entitled “The Tune of Calliope: Poems and Drawings of New York.”

Lishinsky worked passionately as an art therapist, publishing many articles in the field and instructing professional artists and amateurs in the psychiatric treatment of patients through art therapy. He wrote, “The art program I conduct is based on my conviction that art is a wholesome, socially necessary form of work. As in other forms of work and play, consistency, persistence, and purposeful striving must be nourished. The essential nature of art, however, gives genuine artistic work special pertinence to mental health.”*

In 2008 Lishinsky moved into a nursing home and his entire studio, filled with nearly seven decades of work was sold. The collection at Lost Art Salon came by way of this sale.Lishinsky was interviewed in his studio in 2005 and had this to say about his life as an artist: “When I am asked, I say I am 39. I’m really 83. I have no plans to pass away. I’ve lived in Westbeth since 1974. That year, I got divorced. I had a little brownstone on Manhattan Avenue. The whole top floor was my studio.

I had a cousin, Abe Lishinsky, who was a WPA painter. He encouraged me. He said, “Draw whatever you see a lot.” I’ve done that all my life. He said, “Don’t go to the National Academy.” He did that and he felt it crippled him as a painter.

I had a studio off Times Square. At the beginning, I got by doing commercial work. The pay was only $20 to $30 a week, but that was enough. My rent was only $24.50 a month.

When I was 24, I had my first show at the 44th Street gallery. My wife and I were in Provincetown for the summer from 1946 to ‘48. We rented a shack behind a chicken coop.

People in New York City were struggling to make money. I was just satisfied with the money I was making part time so I could exist and keep painting. In order to get a teaching job, you had to have some shows. I had some shows. You had to have write-ups and a point of view. The point of view was cheapening, limiting the expression. You had to give it a name and the name was not enough. That’s what happens to artists. It is not a matter of talent. It is the struggle to get along, the doggedness, sticking to the most intense expression you can get. The struggle to get along and be recognized is what really deflates the spirit.

Gaining acceptability as an artist is mechanical. It is dead. To live, you have to sell your art, but merchandising is cheapening. Merchandising eliminates art that is unpleasant. Unpleasantness is part of life and it has to be shown with what is beautiful. I sell art when I can, but people don’t want to pay. There was this guy, a scenic designer for Balanchine. I made sketches of him. I started a painting of him. He wanted the painting and we agreed to $1000. I reworked the painting and a year passed. He said that he couldn’t afford a thousand dollars. He only wanted to pay $500. That is why I don’t sell.”

*Courtesy of Dylan Foley’s obituary on the artist

Subscribe

Sign up to learn about new collections and upcoming events

Saul Lishinsky was born in 1922 in Carbondale, Illinois. His Russian-Jewish family later moved to the Bronx, and Lishinsky remained in New York City for the rest of this life. Lishinsky served in WWII, and several pieces in the Lost Art Salon Collection feature imagery from his experiences on the front.

Saul Lishinsky was born in 1922 in Carbondale, Illinois. His Russian-Jewish family later moved to the Bronx, and Lishinsky remained in New York City for the rest of this life. Lishinsky served in WWII, and several pieces in the Lost Art Salon Collection feature imagery from his experiences on the front.  Lishinsky was interviewed in his studio in 2005 and had this to say about his life as an artist: “When I am asked, I say I am 39. I’m really 83. I have no plans to pass away. I’ve lived in Westbeth since 1974. That year, I got divorced. I had a little brownstone on Manhattan Avenue. The whole top floor was my studio.

Lishinsky was interviewed in his studio in 2005 and had this to say about his life as an artist: “When I am asked, I say I am 39. I’m really 83. I have no plans to pass away. I’ve lived in Westbeth since 1974. That year, I got divorced. I had a little brownstone on Manhattan Avenue. The whole top floor was my studio.